In 2024, Masjid Sultan marked its bicentennial. For over two centuries, it has served as a cultural and historical landmark in Singapore especially in the Kampong Glam area.

Step into this immersive and interactive exhibition, where history comes to life through the lens of three distinct eras—the 1800s, 1900s, and 2000s. Discover 30 stunning illustrations by local artist Qamar Tahasildar, each woven together with digital interactive elements and oral recordings that unveil the mosque’s profound significance. From its architectural transformations to its vibrant engagement with the local community, this exhibition invites you to explore the enduring legacy of Masjid Sultan.

Interactive Virtual Reality Exhibition

The Foundation Years: 1800s

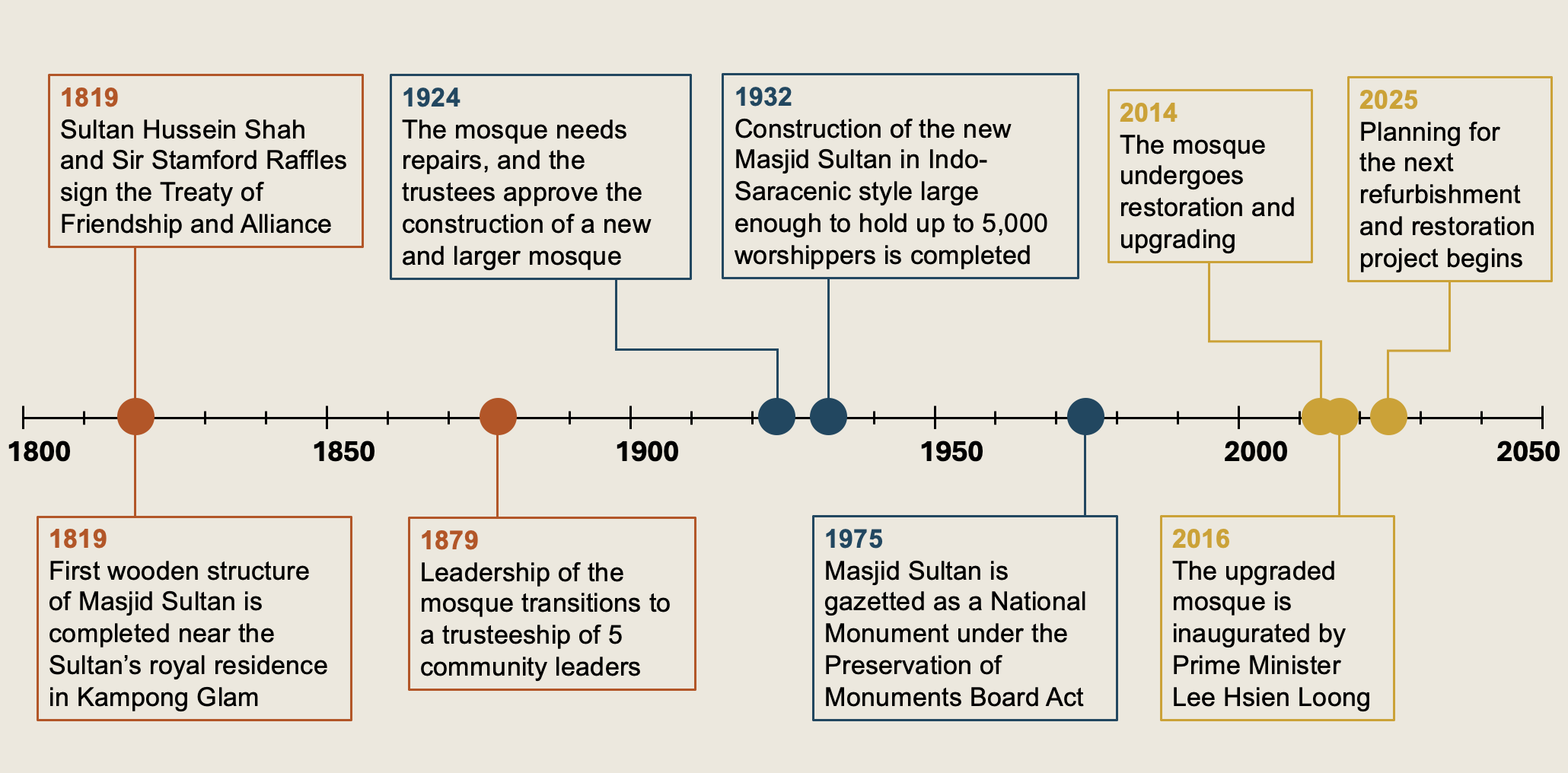

Masjid Sultan’s beginnings can be traced back to 1819, following Sultan Hussein Shah’s agreement with Sir Stamford Raffles. The Treaty of Friendship and Alliance, which allowed the British to establish a trading post in Singapore, was signed in 1819. Sultan Hussein Shah established himself and his entourage at Kampong Glam. The first wooden structure of Masjid Sultan with three-tiered pyramidal roof was constructured in 1819 near the Sultan's royal residence. In 1824, with a contribution of 3,000 dollars from the British East India Company, a brick perimeter verandah was built around the prayer hall and the pengimaman vestibule. The verandah was sheltered by an additional fourth layer, thus making the roof four-tiered.¹

Built beside the Sultan’s palace, it served both as a private place of worship for the royal court and as a public religious centre for the broader Muslim community. As a result, it became widely known as Masjid Sultan, or The Sultan’s Mosque.²

In 1879, further expansion was marked by the donation of land from Sultan Hussein’s grandson, Sultan Alauddin Alam Shah, alongside contributions from community donors. A five-man trusteeship was appointed to look after the mosque.³ The mosque served as a religious and cultural anchor for the growing Muslim population, and a stopover for pilgrims from the Malay Archipelago en route to Mecca.⁴

Remaining largely unchanged for over a century, the mosque played a central role in Islamic life and heritage in Singapore, especially for pilgrims journeying through Kampong Glam. As the community expanded, the mosque continued to embody the shared faith and enduring legacy of the region’s Muslim population.

Change and New Beginning: 1900s

By 1924, the century-old mosque was in need of repairs. The trustees of the mosque approved the construction of a new and larger mosque. As fundraising was ongoing during construction and to avoid disrupting worshippers, the mosque was built in phases and completed in 1932. Designed by Irish architect Denis Santry of Swan & Mclaren, Masjid Sultan’s architecture was heavily influenced by the Indo-Saracenic style. This style combines traditional Indian Mughal and Islamic elements with European architectural features. The mosque is enclosed by a boundary wall of cast-iron railings. The mosque has two gold onion-shaped domes above the eastern and western facades, each topped by a crescent moon and star. The base of each dome is adorned with glass bottle ends donated by members of the Muslim community who were unable to contribute financially to the mosque’s construction. There are minarets on each corner of the mosque with staircases leading to calling towers with balconies. The western façade of the mosque facing North Bridge Road houses the mausoleum of Sultan Alauddin Alam Shah, the grandson of Sultan Hussein Shah.

Within the mosque, the rectangular prayer hall is aligned with the qibla, oriented in the direction of the holy city of Mecca. The two-storey hall is large enough to hold up to 5,000 worshippers.¹³

In 1936, Masjid Sultan became the first in Singapore and the world to install loudspeakers on its minaret, allowing the azan (call to prayer) to be heard from over a mile away. This bold technological adaptation positioned Masjid Sultan as an innovator. However, Singapore’s urban development soon required stricter noise controls. To comply with new regulations, newer mosques built after 1975 directed their speakers inward and the azan began broadcasting on the radio five times a day, a practice that continues today on Warna 94.2FM.¹⁴

The new building was officially opened in 1929 and completed in 1932. Masjid Sultan was later gazetted as a National Monument in 1975 under the Preservation of Monuments Board Act, recognising its historic and architectural significance.¹⁵

Preservation: 2000s

In the 21st century, Masjid Sultan continues to evolve as both a spiritual centre and a cultural landmark. In 2014, the mosque underwent restoration and upgrading that cost an estimated S$3.65 million and took 15 months to complete.²³

While severely damaged parts were replaced, special care was taken to salvage and restore the original timber doors and windows. The domes underwent intensive re-sanding and received four coats of paint. The exterior and interior paint was carefully selected and applied for better long-term maintenance. Elder friendly facilities such as ramps and a translucent glass lift were added while carefully preserving the original character and integrity of the heritage building.²⁴

Religious life remains vibrant. Masjid Sultan offers religious classes, and conducts Friday sermons in both English and Malay, making it accessible to a wide and diverse community. During Ramadan, the mosque and surrounding streets transform into a lively cultural hub. The bustling bazaars along Bussorah Street and Muscat Street attract thousands of visitors for the food stalls, traditional crafts, and performances.²⁵

Beyond worship, the mosque is also an active participant in cultural and interfaith outreach. It is featured in heritage walks, exhibitions, and educational visits organised by institutions like the National Heritage Board.²⁶ Masjid Sultan is one of the three national monuments included in the ‘Kampong Gelam Alliance’, a collective of stakeholders that includes businesses and cultural institutions in the area. This alliance promotes inclusive placemaking efforts, reinforcing Kampong Glam’s identity as a living heritage district.²⁷

Today, Masjid Sultan stands not only as an architectural icon but also as a symbol of Singapore’s multicultural harmony.